Herculaneum is most famous for having been lost, along with Pompeii in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. It is also famous as one of the few ancient cities that can now be seen in almost its original splendour, because unlike Pompeii, its burial was deep enough to ensure the upper storeys of buildings remained intact, and the hotter ash preserved wooden household objects such as beds and doors and even food.

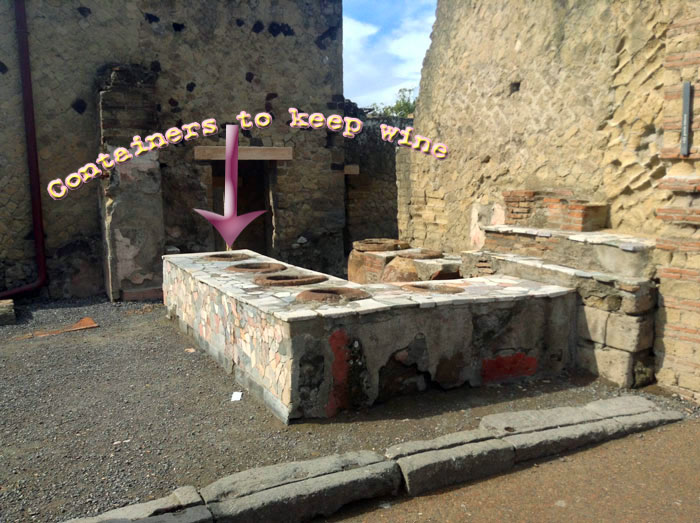

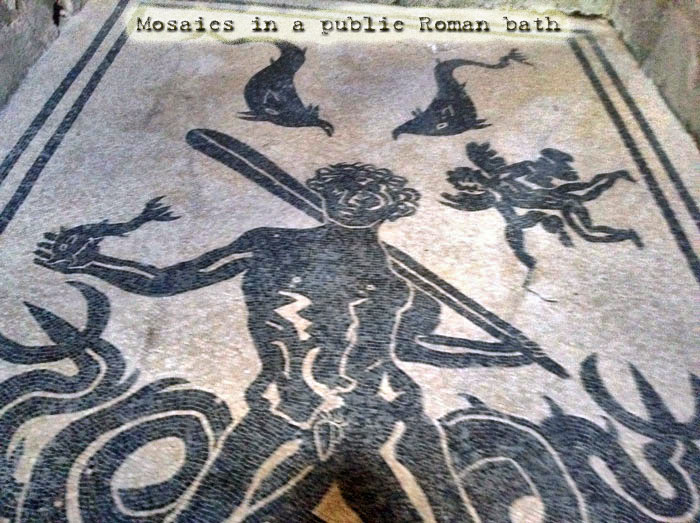

Moreover, Herculaneum was a wealthier town than Pompeii with an extraordinary density of fine houses, and far more lavish use of coloured marble cladding. The discovery in recent years of some 300 skeletons along the seashore came as a surprise since it was known that the town itself had been largely evacuated. While we enjoyed visiting Pompeii, this site was in some ways more fascinating. More compact, you get the feel of a Roman city.

The course and timeline of the eruption can be reconstructed based on archaeological excavations and two letters from Pliny the Younger to the Roman historian Tacitus:

At around 1 pm on the first day of eruption, Mount Vesuvius began spewing volcanic material thousands of metres into the sky. After the plume had reached a height of 27–33 km the top of the column flattened, prompting Pliny to describe it to Tacitus as a stone pine tree. The prevailing winds at the time blew toward the southeast, causing the volcanic material to fall primarily on the city of Pompeii and the surrounding area.

Since Herculaneum lay west of Vesuvius, it was only mildly affected by the first phase of the eruption. While roofs in Pompeii collapsed under the weight of falling debris, only a few centimetres of ash fell on Herculaneum, causing little damage; nevertheless, the ash prompted most inhabitants to flee.

In some ways this was more interesting than Pompeii. It is more compact. It gives you a better sense of life in this town.