Dublin, was founded in 1191.

The General Post Office in Ireland was first located in Hight Street moving toFishamble Street in 1689, to Sycamore Alley in 1709 and then in 1755 to Peter Bardin’s Chocolate House at Fownes Court on the site where the Commercial Buildings used to be. It was afterwards removed to a larger house opposite the Bank of Ireland building on College Green. On 6 January 1818, the new post office in Sackville Street (now O’Connell Street) was opened for business.

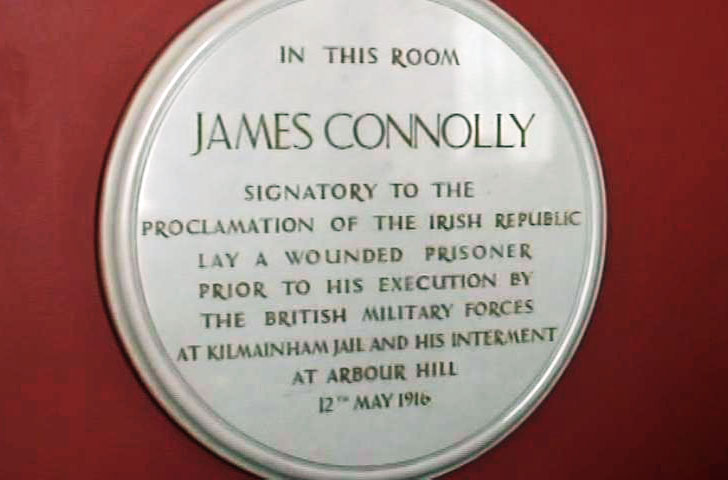

During the Eastern Rising of 1916, the GPO served as the headquarters of the uprising’s leaders. It was from outside this building on 24 April 1916, that Patrick pearse read out the Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

The building was destroyed by fire in the course of the rebellion, save for the granite facade, and not rebuilt until 1929, by the Irish free State government. An original copy of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic was displayed in the museum at the GPO.

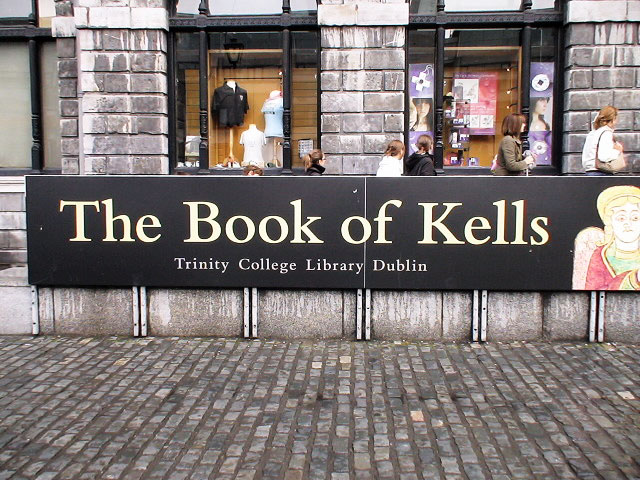

An Irish manuscript containing the Four Gospels, a fragment of Hebrew names, and the Eusebian canons, known also as the “Book of Columba”, probably because it was written in the monastery of Iona to honour the saint. It is likely that it is to this book that the entry in the “Annals of Ulster” under the year 1006 refers, recording that in that year the “Gospel of Columba” was stolen.

According to tradition, the book is a relic from the time of Columba (d. 597) and even the work of his hands, but, on palæographic grounds and judging by the character of the ornamentation, this tradition cannot be sustained, and the date of the composition of the book can hardly be placed earlier than the end of the seventh or beginning of the eighth century. This must be the book which the Welshman, Geraldus Cambrensis, saw at Kildare in the last quarter of the twelfth century and which he describes in glowing terms.

We next hear of it at the cathedral of Kells (Irish Cenannus) in Meath, a foundation of Columba’s, where it remained for a long time, or until the year 1541. In the seventeenth century Archbishop Ussher presented it to Trinity College, Dublin, where it is the most precious manuscript (A. I. 6) in the college library and by far the choicest relic of Irish art that has been preserved.

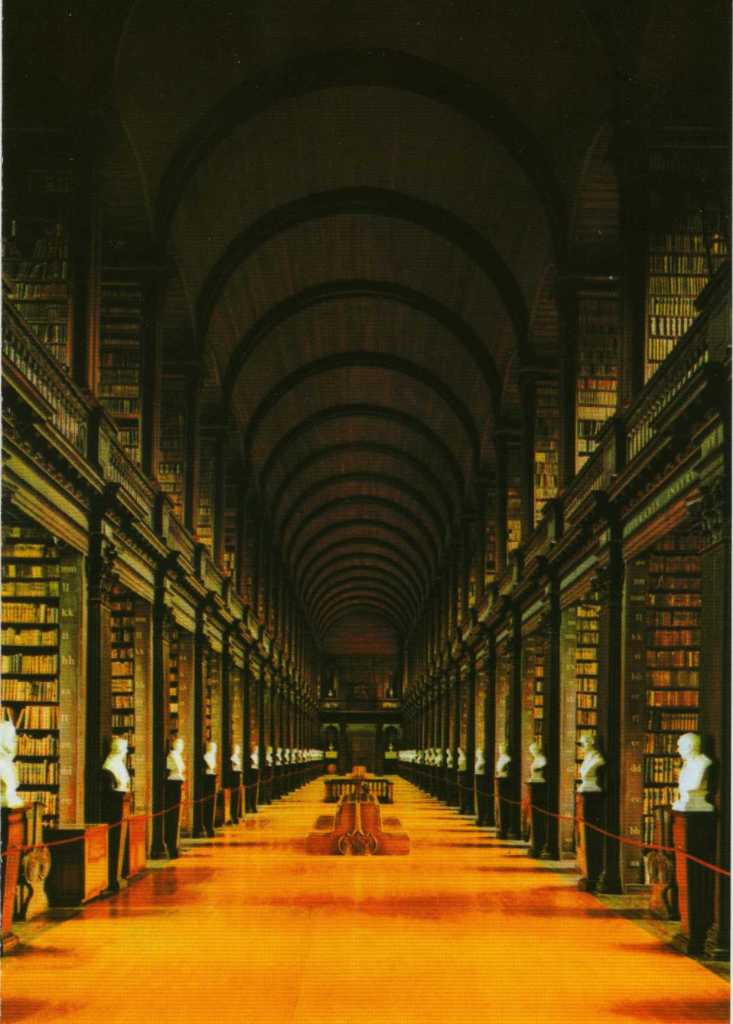

Designed and completed by Thomas Burgh, the Long Room holds 200,000 of the library’s oldest books and manuscripts, including the Book of Kells.

(Note: This a Postcard. No pictures were allowed)

Side entrance to Trinity College located across from the Library.

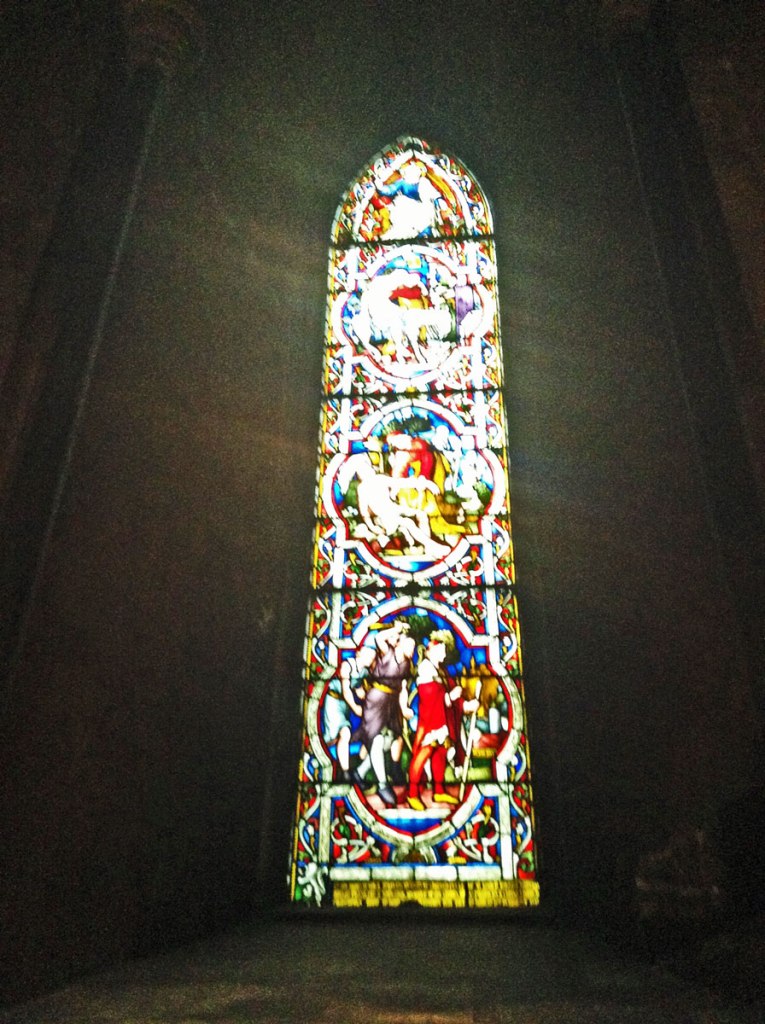

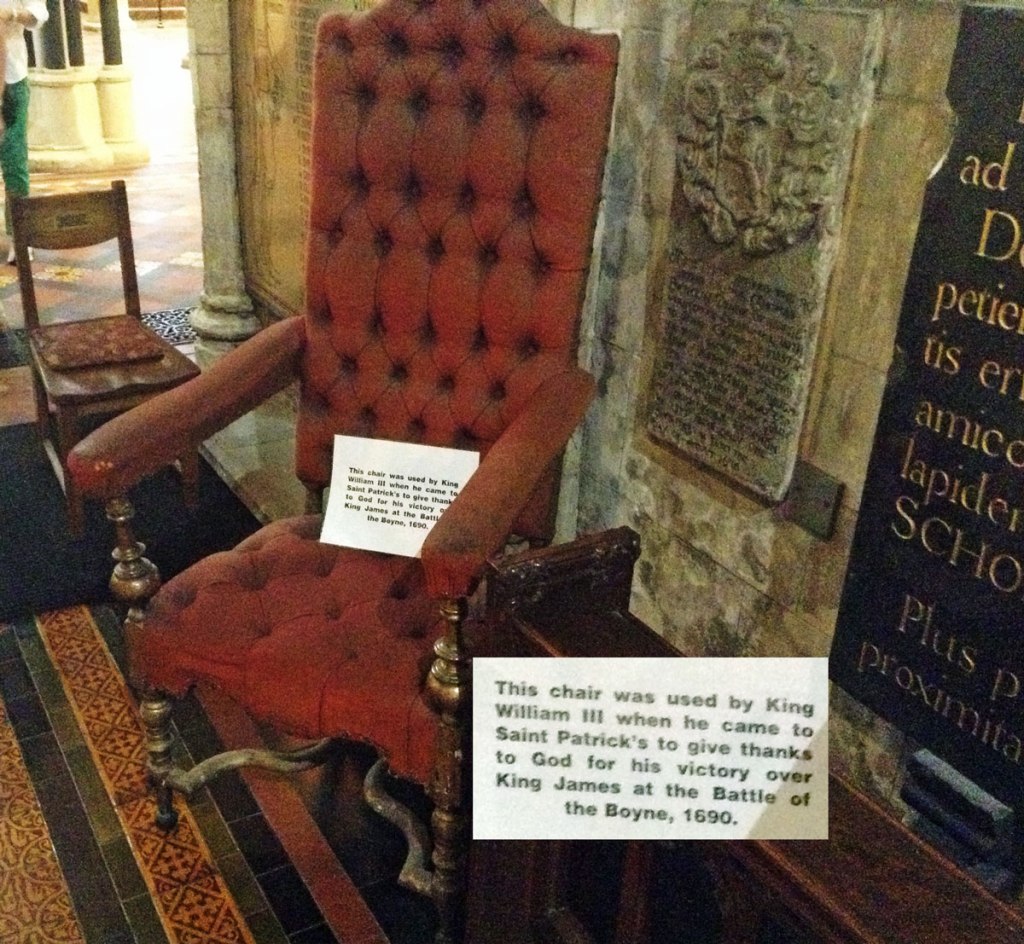

Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, also known as The National Cathedral and Collegiate Church of Saint Patrick,

If you’ve seen the movie Michael Collins you will recognize this building. This was the British headquarters. Irish Republicans were brought through these gates to be interrogated and then sent of to the firing-squad.

View of the main entrance from outside the gates.

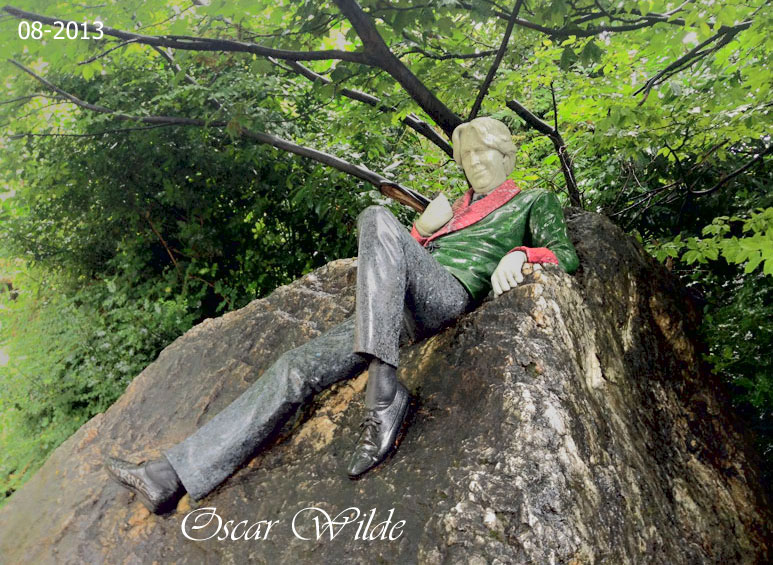

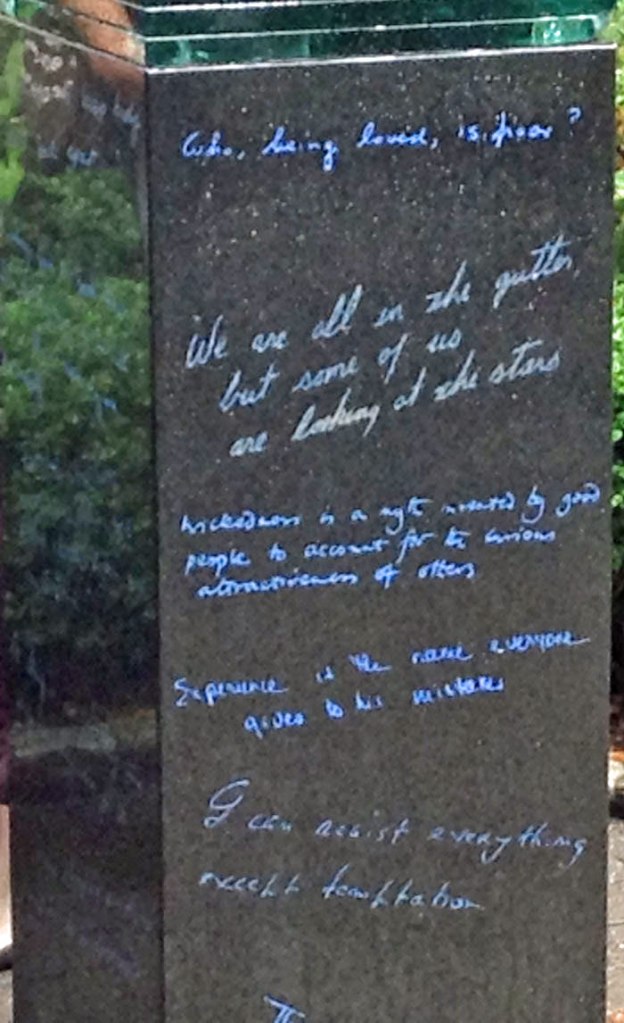

Birthplace of Oscar Wilde in Dublin. We also visited the hotel in Paris where he died.

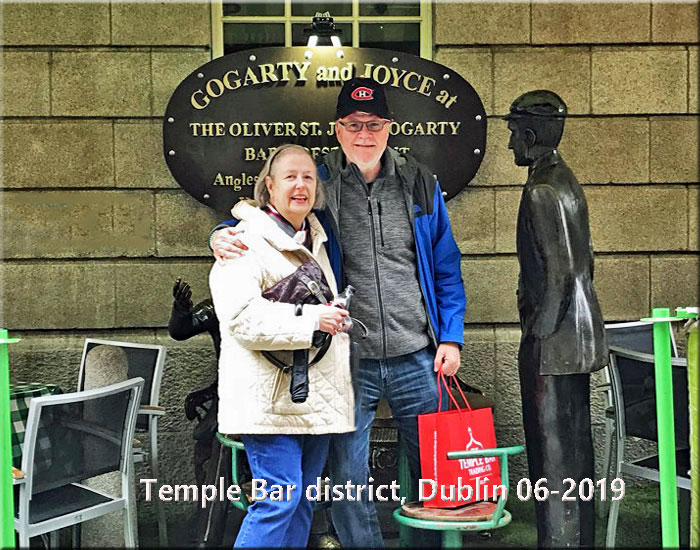

James Joyce stayed at Finn’s Hotel. It is where he met his wife, Nora.

This building is no longer an hotel.

The Dáil has 160 members. The number is set within the limits of the Constitution of Ireland, which sets a minimum ratio of one member per 20,000 of the population, and a maximum of one per 30,000. Under current legislation, members are directly elected for terms not exceeding five years by the people of Ireland under a system of proportional representation known as th single transferable vote.

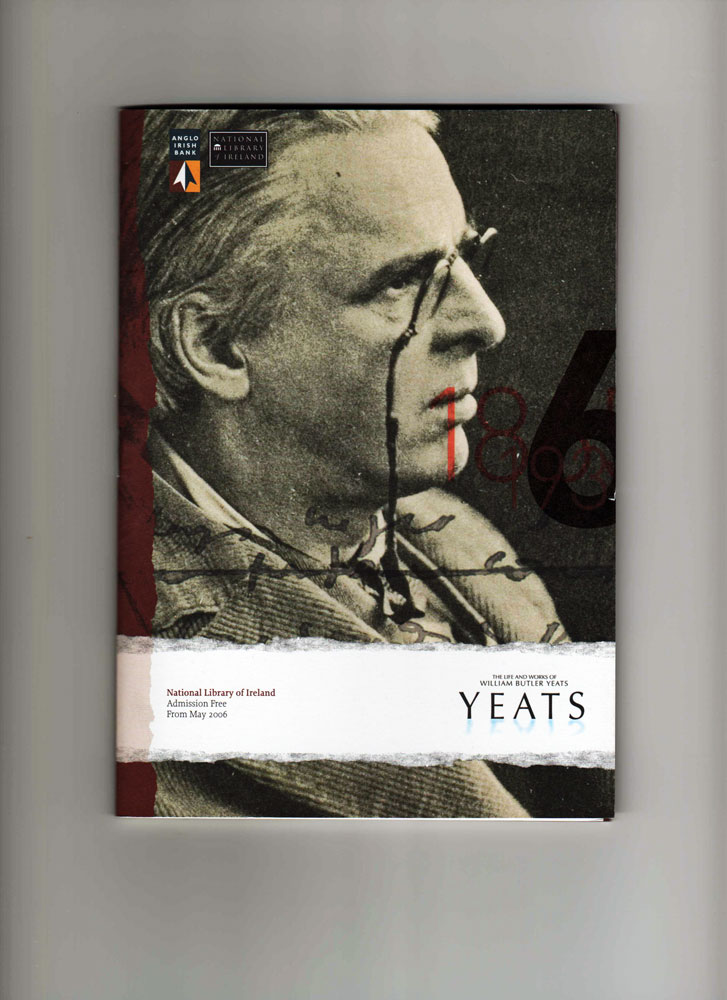

The Dublin Library where we saw a great exhibition on the work of Yeats.

I Have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman’s days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our winged horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road.

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven’s part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse –

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.